Over the last few months, I have been researching and writing a paper for an independent study entitled “Teaching Theology through Worship Ministry in a Postmodern Context.” As a worship pastor, this has been the most important academic study I’ve ever done as far as influencing my personal ministry. Now that I have turned in my first draft of the paper I’m excited to share with you bits and pieces of the paper (It’s 30 pages long, so don’t worry, I won’t be sharing all of it). Overall, I argue that worship ministry is the perfect medium to teach theology to a postmodern culture because it is a ministry characterized by a dialogue with an incarnate God. Part 2 is the last section of the paper in which I propose four strategies for teaching theology through worship ministry to a postmodern generation. I break every blogging rule in the book on the length of this post, but I would really challenge you to read through this critically and give me your feedback. Part 1 is posted here.

…

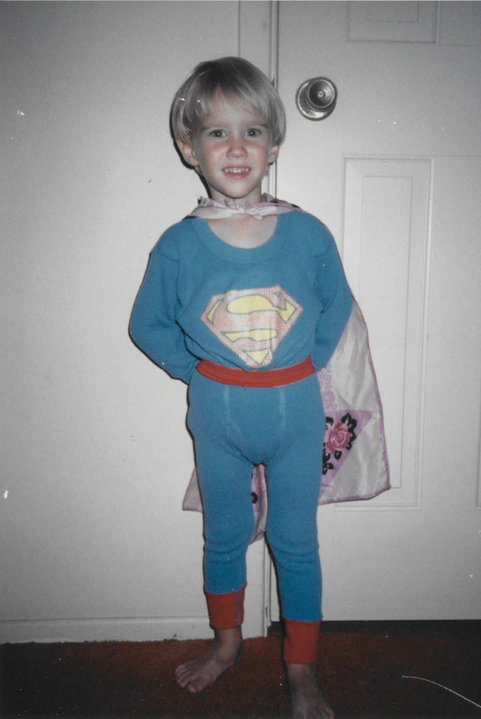

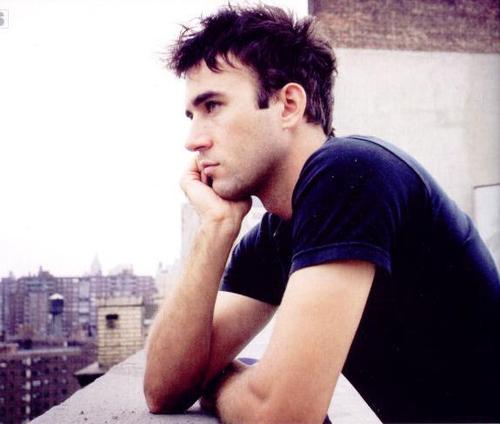

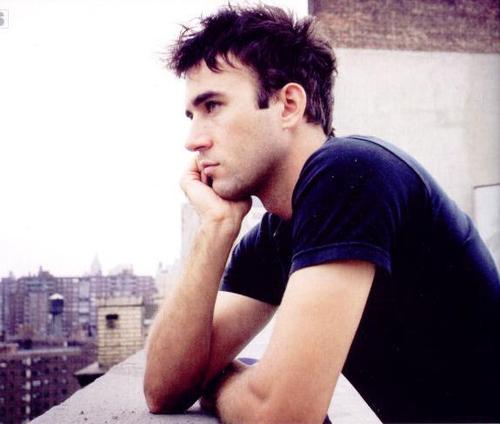

Singer/songwriter genius Sufjan Stevens is a unique blend of spiritual and postmodern in his approach to God in his music. Although he claims no major religious affiliations and certainly does not manifest clear orthodoxy through his songs, there is a sincere desire in his music to engage with a God he longs to be near. In his song, “Oh God, Where are You Now,” Stevens begins by asking God to hold him, to draw near to him as he walks through his draught of faith. In another song off his 2004 album, Seven Swans, entitled, “To Be Alone With You,” Stevens explores the great depths of the implications of atonement, but does it in a very personal, interactive way, that is honest about the underlying doubts inherent in trusting through faith.

Singer/songwriter genius Sufjan Stevens is a unique blend of spiritual and postmodern in his approach to God in his music. Although he claims no major religious affiliations and certainly does not manifest clear orthodoxy through his songs, there is a sincere desire in his music to engage with a God he longs to be near. In his song, “Oh God, Where are You Now,” Stevens begins by asking God to hold him, to draw near to him as he walks through his draught of faith. In another song off his 2004 album, Seven Swans, entitled, “To Be Alone With You,” Stevens explores the great depths of the implications of atonement, but does it in a very personal, interactive way, that is honest about the underlying doubts inherent in trusting through faith.

I’d swim across lake Michigan

I’d sell my shoes

I’d give my body to be back again

In the rest of the room

To be alone with you

To be alone with you

To be alone with you

To be alone with you

You gave your body to the lonely

They took your clothes

You gave up a wife and a family

You gave your goals

To be alone with me

To be alone with me

To be alone with me

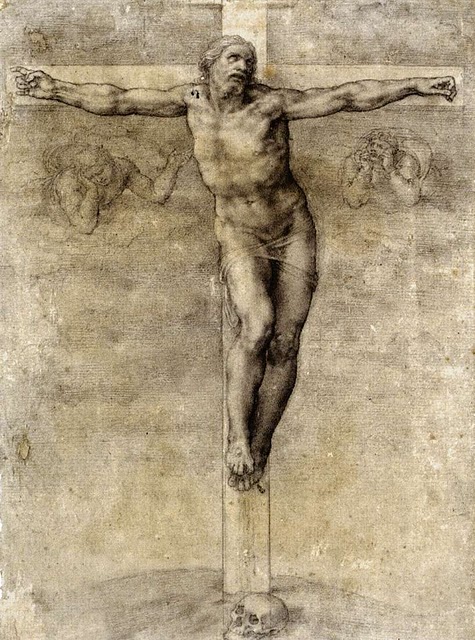

You went up on a tree

To be alone with me you went up on the tree

I’ll never know the man who loved me[2]

It is a mistake to believe that just because postmodern culture has rejected Enlightenment epistemology, that it has no interest in knowing God. As Stevens’ songs express, there are many in the postmodern context who want God to hold them, who want to be alone with the only man who can ever love them completely. But many feel like they can’t know God through the tired recitations, the practiced bullet points, and the reason-entrenched liturgy of the institutional church. But is this the only way to do church? To understand true things about God, is it necessary to recognize them in an auto-legitimizing knowledge system rooted in Enlightenment epistemology? A look at the means by which Ancient Israel and the Early Church engaged with God liturgically and learned about his character says otherwise.

The great hope for the church in the midst of the seemingly hopeless and nihilistic world of the postmodern is the doctrine of Incarnation. Postmodernists can reject metanarrative all they want, Christians know God through Christ! There is no need to fear the multiplicity of interpretation if the interpretation is coming through a walk of faith with an interactive Savior. In order to teach theology in a postmodern context, pastors need to approach it in a way that recognizes our knowledge of God comes through the manifestation of his presence, not the systematic theologies, tomes of dogmatic didactics, and rhetoric driven information. Worship pastors have the opportunity to re-orient and reshape the liturgical structure of the church in such a way that people can dialogue with God. In order to meet the needs of a postmodern culture and teach theology, there must be a reprioritization of dialectic, incarnational liturgy through which the church can know God through interaction.

Before concluding, there are four brief suggestions for practical steps towards a dialectic liturgy that can teach a postmodern church theology. (1) Return to Pre-modern liturgy, (2) contextualization of songs with narrative, (3) the use of deconstructive aesthetics, and (4) the aesthetic of justice.

The sacramental imagination begins from the assumption that our discipleship depends not only—not even primariliy—on the conveyance of ideas into our minds, but on the immersion in embodied practices and rituals that form us into the kind of people God calls us to be.[3]

1. A Return to Pre-modern Liturgy

1. A Return to Pre-modern Liturgy

James Smith, in concluding his discussion of postmodernism and the church writes, “The outcome of postmodernism…should be a robust confessional theology and ecclesiology that unapologetically reclaims pre-modern practices in and for a postmodern culture.”[4] Pre-modern liturgy is one founded on Incarnation, not Reason. Before the Enlightenment, people could know things without knowing them objectively, they could embrace faith without fear of it seeming unreasonable. Now that the man behind the curtain of Modern thinking has been exposed, Smith concludes that there is nothing stopping the church from returning to a dialectic liturgy centered on Incarnation and driven by faith.

As is seen in a look at Ancient Israel and the Early Church, there is great precedence for knowing God through dialectic media. A return to practices such as the interactive taking of the Lord’s Supper, the dialectic interaction that takes place through participation in the traditional church calendar, and the communal sharing of stories about God’s interaction in their life can create strong dialectic liturgy that both praises God and forms believers’ understanding of him. As Marva Dawn writes, “The church’s catechumenal process forms us all—both the new in faith and the more mature—to be a people who drink exuberantly of the satisfying Water of life to quench our deepest thirst.”[5] The Lord’s Supper causes the church to interact with the God who saved them and the church surrounding them in a way that forms an understanding of God. Participating in things like Lent can teach Christians their poverty that led to the cross and the value of sacrificing for Christ, much like Ancient Israel knew God through the daily habits formed by Law-living. Recounting stories, both biblical and personal, can promote a dialogue with an interactive God that teaches truths about Him.

2. Contextualize Songs With Narrative

2. Contextualize Songs With Narrative

Music as a mode of both worship and teaching of theology, as discussed earlier, is an important part of both modern worship ministry and historical liturgy. However, modern worship music can often times feel like stars floating aimlessly through space, unaware of the galaxy surrounding them. It is good for the church to sing, “Our God is greater,” but the phrase doesn’t mean as much when understood outside of the context of the narrative that expresses that truth about God. Without the narrative surrounding the songs sung in a liturgical setting, musical worship becomes rhetorical, merely affirming truths about God and not truly interacting with the God of truth.

In order to connect worship songs effectively to a postmodern culture in a didactic way, the singing of them must happen in a dialectic context. This means contextualizing songs with either the biblical narrative surrounding them or the narrative of the church. Lee Wyatt, although writing primarily about preaching in a postmodern context, still makes an appropriate point. “If we allow the shape of the Story to inform our preaching, then we will be primarily storytellers. No longer will we simply dip into the Scriptures to find a text, or use lectionary readings in isolation from their larger contexts. Specific texts will be embedded in a larger Story.”[6]

Likewise, specific songs need to be embedded in the larger Story of faith. As a worship pastor, before leading the church through a series of songs about God’s faithfulness, I might try and share the story of God bringing his people back from exile, or talk about Jesus’ faithfulness to Peter despite Peter’s denial of him, or have a member of the congregation come and share her story of God’s faithfulness in her own life. By contextualizing songs in narrative, a liturgy that is currently rhetorical becomes dialectic again. Just as Moses sang out of response to God’s presence and interaction, the church is singing in a response to the narrative they inhabit. This simple addition to the current worship form of many Evangelical churches would turn music into a strong dialectic liturgy and a powerful didactic tool to a postmodern culture.

3. Deconstructive Aesthetics

3. Deconstructive Aesthetics

John Caputo describes deconstruction as the “hermeneutics of the Kingdom of God.”[7] What he means is that the kingdom of God, the advent of Jesus in the world, is the deconstructive force that tears down the systems of self and idolatry characterizing the world and reconstructs it in the image of Christ. He writes, “In my view, deconstruction is good news because it delivers the shock of the other to the forces of the same, the shock of the good (the “ought”) to the forces of being (“what is”), which is also why I think it bears good news to the church.”[8] In Caputo’s conclusion, he describes a “church” in Ireland called Ikon, which exemplifies the idea of incorporating a deconstructive aesthetic to create a dialectic liturgy. In its service there are interpretive readings and dance, plays expressing the darkness preceding the resurrection, dramatic iconography asking questions about forgiveness and acceptance of gays and lesbians, pallets and paints available for people to respond and an ultimate suspension of judgment for the sake of all entering into God’s presence.[9]

This, even by Caputo’s admission, is an extreme example of postmodern liturgy that would be difficult for many Christians, even Liberal ones, to enjoy participating in. However, it does show the powerful effect deconstructive aesthetics can have in helping people engage with God. A more palatable example of deconstructive aesthetic is Rob Bell’s series of devotional videos called Nooma. The videos range from two minutes to thirty minutes and usually consist of a series of questions or statements that invoke the viewer to work through the truth of God for himself. In these videos, theology is not normally explicitly expressed but rather inferred through its deconstructive presentation.

Deconstructive aesthetic is any form of art that causes the receiver to actively engage with God. It is a prophetic voice calling the church out of her slumber into an active dialogue with her Redeemer. In order to create a dialectic liturgy in a postmodern context, art must not merely be used as passive reflections on truth, but active deconstructions that invoke interactions.

4. The Aesthetic of Justice

4. The Aesthetic of Justice

Smith in his conclusions about a radical orthodox church writes, “The Christian ekklesia must be not only liturgical but also local; it must transform not only hearts but also neighborhoods; its worship must foster not only discipleship but also justice—indeed, disciples who are passionate about justice.”[10] During the research for this paper, I was surprised by the descriptions given by postmodern theologians like James Smith, John Caputo, and Merold Westphal of what postmodern liturgy should look like. It seems the assumption they make about postmodern culture is that it is a culture filled with highly educated people with nuanced artistic tastes. Although that does describe a small part of them, it is not characteristic of them all. In fact, the majority of postmodern culture is comprised of people who would find radical forms of deconstructive art off-putting. It is for this reason that I would like to suggest something new to be thrown into the discussion for what postmodern liturgy should look like. It is the aesthetic of justice.

I am currently a worship pastor at a church called Fellowship White Rock in Dallas, TX. It is a new church started a year ago as a parish offshoot of the church Fellowship Bible Church Dallas. As an attempt to engage a postmodern culture with a dialectic liturgy, the teaching pastor and I decided to change the traditional structure of Sunday services to incorporate the aesthetic of justice into our common liturgy. Every fourth Sunday of the month, instead of the preaching and singing, instead of communion and story, we serve the community in which we inhabit. Since we meet in an underprivileged, underachieving school, there have been numerous ways to serve the community in meaningful ways. Doing things like planting a vegetable garden, hosting block party celebrations for the school kids, and even refurnishing the home of a student who lost all he had in an apartment fire, our church is actively engaging in making right the physical, community wrongs we see around us.

The people who go to our church, for the most part don’t look like radical postmodernists. Although educated, they are mainly young professionals who couldn’t recognize the beauty of a Jackson Pollock painting if it punched them in the face (which could happen). However, they are postmodern and recognize the beauty of seeking justice for the people around them. They are learning that God is a God who transforms people groups, that God’s grace seeks justice, that God’s people should be blessings to those around them. They are learning that the Gospel is both a now and not yet transformational force. In order to create a dialectic liturgy through deconstructive aesthetics, pastors need to think beyond the traditional realm of art and explore the more accessible aesthetic of social justice.

[1] Sufjan Stevens, “Oh God, Where are You Now? (In Pickeral Lake, Pigeon, Marquette? Mackinaw?),” Greetings from Michigan, comps. Sufjan Stevens, 2003,.

[2] Sufjan Stevens, “To Be Alone With You,” Seven Swans, comps. Sufjan Stevens, 2004,.

[5] Marva Dawn, A Royal “Waste” of Time (Grand Rapids: WIlliam B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), p. 251.

On the other hand, there are those who embrace every aspect of the modern. They have multi-media presentations on the highest quality projectors money can buy. Their bands are made of all studio musicians and the light shows rival broadway.

On the other hand, there are those who embrace every aspect of the modern. They have multi-media presentations on the highest quality projectors money can buy. Their bands are made of all studio musicians and the light shows rival broadway.